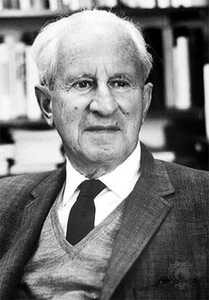

Herbert Marcuse on the ideology of death

Although critical philosophers like Herbert Marcuse (1898 – 1979) are not known for their contributions to economics or analytic philosophy, Marcuse’s essay “The Ideology of Death” (1952) should appeal to those who think that death is not a necessary part of existence, let alone something to celebrate. In this essay, the author discusses the phenomenon that prominent Western philosophers (Plato, Hegel, Heidegger) have not just accepted death as a biological fact that may be overcome, but have elevated its status to something that gives meaning to life. Unfortunately, this line of thinking persists today. Although Herbert Marcuse lived through the 60’s and 70’s, he did not seem to have an interest in investigating scientific means to prolong life and overcome death.

Although critical philosophers like Herbert Marcuse (1898 – 1979) are not known for their contributions to economics or analytic philosophy, Marcuse’s essay “The Ideology of Death” (1952) should appeal to those who think that death is not a necessary part of existence, let alone something to celebrate. In this essay, the author discusses the phenomenon that prominent Western philosophers (Plato, Hegel, Heidegger) have not just accepted death as a biological fact that may be overcome, but have elevated its status to something that gives meaning to life. Unfortunately, this line of thinking persists today. Although Herbert Marcuse lived through the 60’s and 70’s, he did not seem to have an interest in investigating scientific means to prolong life and overcome death.

In the history of Western thought, the interpretation of death has run the whole gamut from the notion of a mere natural fact, pertaining to man as organic matter, to the idea of death as the telos of life, the distinguishing feature of human existence. From these two opposite poles, two contrasting ethics may be derived; On the one hand, the attitude toward death is stoic or skeptic acceptance of the inevitable, or even the repression of the thought of death by life; on the other hand the idealistic glorification of death is that which gives “meaning” to life, or is the precondition for the “true” life of man…

It is remarkable to what extent the notion of death as not only biological but ontological necessity has permeated Western philosophy–remarkable because the overcoming and mastery of mere natural necessity has otherwise been regarded as the distinction of human existence and endeavor…

A brute biological fact, permeated with pain, horror, and despair, is transformed into an existential privilege. From the beginning to the end, philosophy has exhibited this strange masochism–and sadism, for the exaltation of one’s own death involved the exaltation of the death of others…

How can one protest against death, fight for its delay and conquest, when Christ died willingly on the cross so that mankind might be redeemed from sin? The death of the son of God bestows final sanction on the death of the son of man…

The fight against disease is not identical with the fight against death. There seems to be a point at which the former ceases to continue into the latter. Some deep-rooted mental barrier seems to arrest the will before the technical barrier is reached. Man seems to bow before the inevitable without really being convinced that it is inevitable.

Published in The Meaning of Death, Herman Feifel, Editor (1959)